A home for the eternal guru

Historian Kathryn Hurlock heads to the Indian state of Punjab to unlock the Sikh's holiest pilgrimage destination.

Published 29 July 2025

In April 2004, the Times of India ran a news story about a specially chartered flight leaving the airport at Amritsar, a city of about one million people in the north-western Indian province of Punjab. Those on board were heading for Toronto’s Pearson International Airport and travelling in some style, all 150 of them carried across the tarmac to the plane on luxurious cushions, draped in shawls and delivered to their reserved seats by specially selected attendants. They had already been carried on the heads of the same men past crowds of joyous people as they left the city, and were seen off by high officials and members of the Sikh faith. People showered the procession with petals and handed out gifts of biscuits, fruit and religious photographs. Displays of swordsmanship entertained the crowds, and groups of smiling schoolchildren dutifully lined up to wish the passengers well. When they arrived in Toronto many hours later, the plane was met by the Canadian prime minister, Paul Martin, and Canada’s Sikh leaders. From there they were taken to a gurdwara, a Sikh place of worship, before travelling to other gurdwaras across the country.

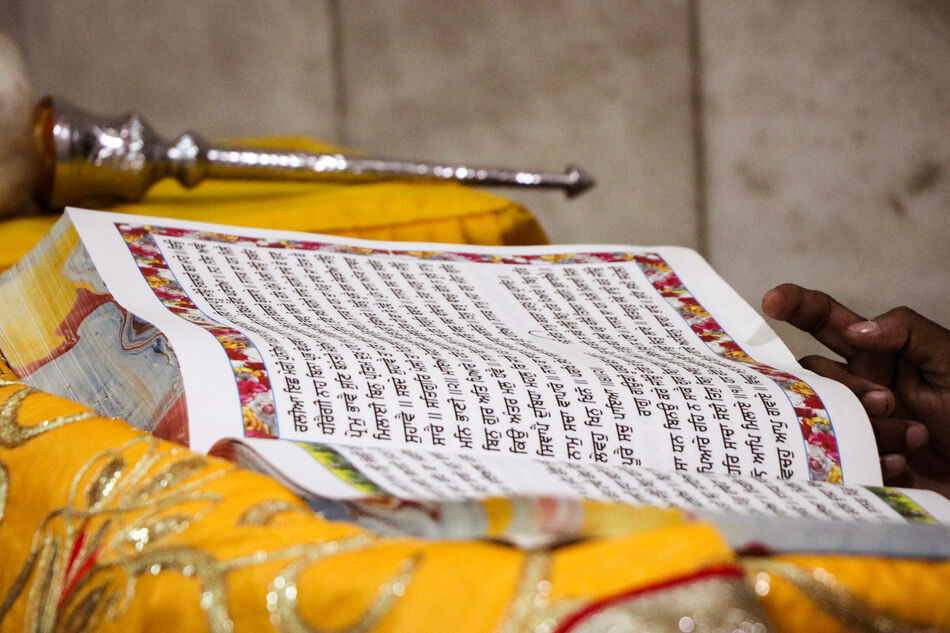

Each one of the ‘passengers’ was a copy of the Guru Granth Sahib, the holy book of the Sikh faith. This is revered as a living eternal guru, the source of all spiritual wisdom and advice on how to live. The copies needed by the Canadian Sikhs had to come from Amritsar as nowhere else in the world is allowed to make them, and had to be transported with due reverence. In the city itself, the original Granth Sahib, a collection of texts by the first ten gurus of Sikhism, is kept in the Harmandir or Golden Temple, the holiest place in the Sikh world. Given Amritsar’s importance as the home of the Granth Sahib, the Harmandir and the tank of sacred water which surrounds it, it is not surprising that it is the Sikhs’ most important pilgrimage destination too.

Amritsar was never intended as a pilgrimage centre by the faith’s founder, Guru Nanak (1469–1539). Born in what is now Pakistan, Nanak was a married clerk and father of two, an otherwise unremarkable man when he disappeared while bathing with a friend in the river. When he emerged unscathed several days later, he declared, ‘There is neither Hindu nor Muslim,’ and established his own religion. Nanak left his job and embarked on a long tour around India, preaching and singing of his new beliefs. When he eventually returned home, Nanak took his family and founded a new settlement at Kartarpur. People flocked to hear him preach, and he left behind him a community who had settled around him. From there he set off for the place that later became Amritsar, just over thirty miles south of his home: his destination may have been a lake where he simply hoped to meditate. The place was virtually uninhabited, surrounded by forest.

It was only after Guru Nanak died that Amritsar became a place of pilgrimage in his honour, even though Nanak had not been a great advocate of pilgrimage. He thought it ‘barely worth a sesame seed’ unless people undertook some form of internal spiritual pilgrimage beforehand. ‘Why should I bathe at sacred shrines of pilgrimage?’ he asked rhetorically. ‘My pilgrimage is spiritual wisdom within, and contemplation on the Shabad.’ Even so, he did single out one pool as a special place, which was so effective it was called the ‘pool of the nectar of immortality’ by Guru Nanak in his poetry. He told his followers, ‘sins are washed away by bathing in Amritsar’. Whether he meant the pool at Amritsar in a literal (the water) or metaphorical (bathing the mind in spiritual teaching) sense is debatable. Clearly many have taken his statement literally, and this has made the site important enough to become the home of the Sikh gurus and the location of its eternal guru, the Granth Sahib. Despite this, the influential Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee refuses to acknowledge pilgrimage as part of Sikhism, perhaps because it seems uncomfortably close to Hindu practice. Perhaps someone should tell that to the thousands who flock to Amritsar every year?

From Holy Places: How Pilgrimage Changed the World Profile Books, hardback, 464pp